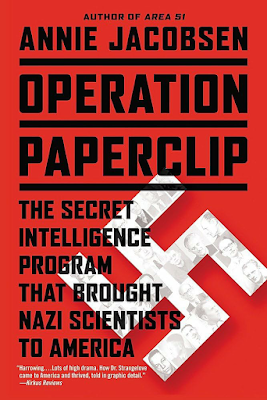

"Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America" By Annie Jacobsen (2014).

An excerpt from the book - Chapter Seven: Hitler’s Doctors:

During the war, physicians with the U.S. Army Air Forces heard rumors about cutting-edge research being developed by the Reich's aviation doctors. The Luftwaffe was highly secretive about this research, and its aviation doctors did not regularly publish their work in medical journals. When they did, usually in a Nazi Party-sponsored journal like Aviation Medicine (Luftfahrtmedizin), the U.S. Army Air Forces would circumvent copyright law, translate the work into English, and republish it for their own flight surgeons to study. Areas in which the Nazis were known to be breaking new ground were air-sea rescue programs, high-altitude studies, and decompression sickness studies. In other words, Nazi doctors were supposedly leading the world's research in how pilots performed in extreme cold, extreme altitude, and at extreme speeds.At war's end, there were two American military officers who were particularly interested in capturing the secrets of Nazi-sponsored aviation research. They were Major General Malcolm Grow, surgeon general of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, and Lieutenant Colonel Harry Armstrong, chief surgeon of the Eighth Air Force. Both men were physicians, flight surgeons, and aviation medicine pioneers. Before the war, Grow and Armstrong had cofounded the aviation medicine laboratory at Wright Field, where together they initiated many of the major medical advances that had kept U.S. airmen alive during the air war. At Wright Field, Armstrong perfected a pilot-friendly oxygen mask and conducted groundbreaking studies in pilot physiology associated with high-altitude flight. Grow developed the original flier's flak vest-a twenty-two-pound armored jacket that could protect airmen against antiaircraft fire. Now, with the war over, Grow and Armstrong saw unprecedented opportunity in seizing everything the Nazis had been working on in aviation research so as to incorporate that knowledge into U.S. Army Air Force's understanding.According to an interview with Armstrong decades later, a plan was hatched during a meeting between himself and General Grow at the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe headquarters, in Saint-Germain, France. The two men knew that many of the Luftwaffe's medical research institutions had been located in Berlin, and the plan was for Colonel Armstrong to go there and track down as many Luftwaffe doctors as he could find with the goal of enticing them to come to work for the U.S. Army Air Forces. As surgeon general, Grow could see to it that Armstrong was placed in the U.S-occupied zone in Berlin, as chief surgeon with the Army Air Forces contingent there. This would give Armstrong access to a city divided into U.S. and Russian zones. General Grow would return to Army Air Forces headquarters in Washington, D.C., where he would lobby superiors to authorize and pay for a new research laboratory exploiting what the Nazi doctors had been working on during the war. With the plan set in motion, Armstrong set out for Berlin.The search proved difficult at first. It appeared as if every Luftwaffe doctor had fled Berlin. Armstrong had a list of 115 individuals he hoped to find. At the top of that list was one of the Reich's most important aviation doctors, a German physiologist named Dr. Hubertus Strughold. Armstrong had a past personal connection with Dr. Strughold.

"The roots of that story go back to about 1934," Armstrong explained in a U.S. Air Force oral history interview after the war, when both men were attending the annual convention of the Aero Medical Association, in Washington, D.C. The two men had much in common and "became quite good friends." Both were pioneers in pilot physiology and had conducted groundbreaking high-altitude experiments on themselves. "We had some common bonds in the sense that he and I were almost exactly the same age, he and I were both publishing a book on aviation medicine that particular year, and he held exactly the same assignment in Germany that I held in the United States," Armstrong explained. The two physicians met a second time, in 1937, at an international medical conference at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City. This was before the outbreak of war, Nazi Germany was not yet seen as an international pariah, and Dr. Strughold represented Germany at the conference. The two physicians had even more in common in 1937. Armstrong was director of the Aero Medical Research Laboratory at Wright Field, and Strughold was director of the Aviation Medical Research. Institute of the Reich Air Ministry in Berlin. Their jobs were almost identical. Now, at war's end, the two men had not seen one another in eight years, but Strughold had maintained the same high-ranking position for the duration of the war. If anyone knew the secrets of Luftwaffe medical research, Dr. Hubertus Strughold did. In Berlin, Harry Armstrong became determined to find him.One of the first places Armstrong visited was Strughold's former office at the Aviation Medical Research Institute, located in the fancy Berlin suburb of Charlottenburg. He was looking for leads. But the once-grand German military medical academy, with its formerly manicured lawns and groomed parks, had been bombed and was abandoned. Strughold's office was empty. Armstrong continued his journey across Berlin, visiting universities that Strughold was known to be affiliated with. Every doctor or professor he interviewed gave a similar answer: They claimed to have no idea where Dr. Strughold and his large staff of Luftwaffe doctors had gone.At the University of Berlin, Armstrong finally caught a break when he came across a respiratory specialist named Ulrich Luft, teaching a physiology class to a small group of students inside a wrecked classroom. Luft was unusual- looking, with a shock of red hair. He was tall, polite, and spoke perfect English, which he had learned from his Scottish mother. Ulrich Luft told Harry Armstrong that the Russians had taken everything from his university laboratory, including the faucets and sinks, and that he, Luft, was earning money in a local clinic treating war refugees suffering from typhoid fever. Armstrong saw opportunity in Luft's predicament and confided in him, explaining that he was trying to locate German aviation doctors in order to hire them for U.S. Army-sponsored research. Armstrong said that, in particular, he was trying to find one man, Dr. Hubertus Strughold. Anyone who could help him would be paid. Dr. Luft told Armstrong that Strughold had been his former boss.

According to Luft, Strughold had dismissed his entire staff at the Aviation Medical Research Institute in the last month of the war. Luft told Armstrong that Strughold and several of his closest colleagues had gone to the University of Göttingen. They were still there now, working inside a research lab under British control. Armstrong thanked Luft and headed to Göttingen to find Strughold. Whatever the British were paying him, Armstrong figured he would be able to lure Strughold away because of their strong personal connection. There was also a great deal of money to be made pending the authorization of the new research laboratory. Armstrong and Grow's plan meant hiring more than fifty Luftwaffe doctors. There was a lot of work to be had, not just for Strughold but for many of his colleagues as well.

Video Title: The Dark History of Operation Paperclip: How the US Recruited Remorseless Nazi Scientists | IRONCLAD. Source: IRONCLAD. Date Published: August 3, 2023.