Wikipedia:

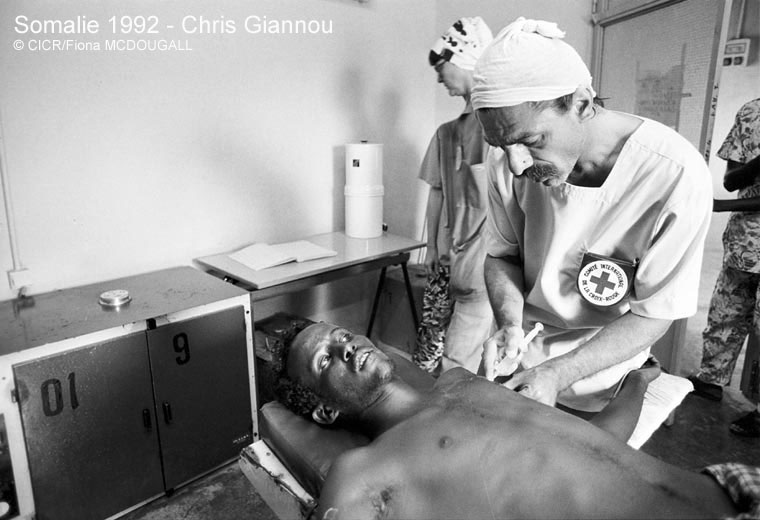

Chris Giannou (born 1949) is a Greek Canadian war surgeon and served chief surgeon for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) until December 2006.Title: The Failure of the Post-Colonial State in the Middle East: A Conversation with Chris Giannou. Source: DU Center for Middle East Studies. Date Published: April 29, 2014. Description:

Giannou left his official post with the ICRC after 7 years as the head of Unit Surgery, and today carries out international surgical missions around the world on their behalf. He is the topic of the Cineflix film "On the Border of the Abyss" which covers his lifetime of work in helping less-fortunate people and in mastering the concepts of war surgery. The documentary was aired, as "War Surgeon: Chris Giannou", by the Canadian public television station TVO on 10 April 2002. Recently, Giannou was the lead author on a new War Surgery book published by the International Committee of the Red Cross. Volume 1 of the book, called "War Surgery: Working with Limited Resources in Armed Conflict and Other Situations of Violence" is currently available on the ICRC website. He continues to inspire many to become war surgeons.

On April 4, 2014, the Center for Middle East Studies was honored to host an afternoon discussion with Chris Giannou, longtime war surgeon and former Head of Unit Surgery for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Dr. Giannou has led a distinguished medical career through some of the world's most dangerous conflicts: in Lebanon, Somalia, Chechnya, Liberia, Afghanistan, and Iraq. He is author of Besieged: A Doctor's Story of Life and Death in Beirut (1991) and lead author of War Surgery: Working with Limited Resources in Armed Conflict and Other Situations of Violence (2009). The event was made possible by the University of Denver's Center on Rights Development, at whose annual symposium Dr. Giannou gave the closing keynote address."The failure of the post-colonial state throughout the region is largely a failure of a certain type of modernization. The third alternative to that is simply, well, let's accept the Western values, even today of neo-liberalism, and let's make money. Now, that works for a minority, it does not work for ninety-nine percent of the population. And if modernity is simply the equivalence of the consumer society then it's a very, very poor modernization.

Because modernity in Western Europe, beginning two-three centuries ago, is a slow development of the rule of law, the separation of state and religion, rule by law and not rule by personality. Now, that's a problem not only in Middle East and Northern Africa. I'm of Greek origin, and I live today in Greece. Well, the post-Ottoman state in Greece is the same. There's no rule of law, it's the rule of personalities, we still have not separated state and religion, we still have problems with language. . . In effect, what you have is an on-going renaissance, and many of these questions, also constitutional, monarchy or republic, that Europe went through over several centuries, Renaissance and Enlightenment, creating the modern era. . . Whether it's Greece, whether it's ex-Yugoslavia, the Balkans, again, post-Ottoman empire, whether it's the Middle East, North Africa, we have not managed to do that. And the result is that for many people today modernization is simply the consumer society.

So you see people in the streets, whether it's Athens, Beirut, Alexandria, or Algiers, and they dress like Europeans, they appear even to act like Europeans. The image of women in the Arab world all of them wearing a scar over their heads, or burka, or chador, etc, etc, is rubbish. There is a great deal more of it today than twenty-five years ago, but a very common scene, not even in Beirut, but in Southern Lebanon, two sisters sitting at an outdoor cafe, one covered, the second wearing a mini-skirt, and they're having coffee and ice-cream at an outdoor cafe. And they're sisters. Now that apparent contradiction is all about a society going through the convulsions of modernization.

When I was in medical school in the 70s in Cairo, and in 79, therefore, just after the Islamic Revolution in Iran, more and more women started wearing the hijab. It was still a very small minority. But many of them said wearing the hijab gives me freedom because I'm no longer a sex object. And when you look at the sexualization of adolescents in America or Europe, even pre-adolescents, sexualization of little girls, well that's obviously demeaning in my opinion. I'm a feminist, I'm actually a radical feminist. And I find it demeaning. And I really don't like seeing, you know, women's underwear, their strings, and this and that, because their jeans are half way down to their knees, because I think that's demeaning, and I don't think it's an expression of freedom.

It's an expression simply of the present consumer society and marketing. So if you are a non-Western woman, and you want to be modern, and you want to be considered as a human being and not as a sex object, then one way is to wear the hijab. Now, there's also a great deal of hypocrisy behind the wearing of the hijab. But I also understand the explanation of certain women that this way men are obliged to deal with me as a human being with a brain, with ideas. And, again, as I said, this is the challenge of modernization. How do you modernize without losing your traditions? How do you become Japanese? And the Arab-Muslim World has not been able to find that, neither through the secular-modernizing currents of thought and ideology, neither through Islam, nor simply 'well, let's accept Western values and the consumer society.' So they're at a sort of dead-end." - Chris Giannou [25:35 - 32:11].