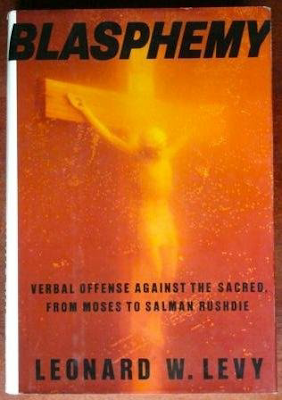

"Blasphemy: Verbal Offense Against the Sacred, From Moses to Salman Rushdie" by Leonard W. Levy (1995).

Leonard Williams Levy (April 9, 1923 – August 24, 2006) was an American historian, the Andrew W. Mellon All-Claremont Professor of Humanities and chairman of the Graduate Faculty of History at Claremont Graduate School, California, who specialized in the history of basic American Constitutional freedoms. He was born in Toronto, Ontario, and educated at the University of Michigan as an undergraduate and at Columbia University, where his mentor for the Ph.D. degree was Henry Steele Commager.

Levy's most honored book was his 1968 study Origins of the Fifth Amendment, focusing on the history of the privilege against self-incrimination. This book was awarded the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for History. He wrote almost forty other books, such as The Establishment Clause, Treason Against God: A History of the Offense of Blasphemy, Blasphemy: Verbal Offenses Against the Sacred, from Moses to Salman Rushdie, and Religion and the First Amendment. He also was editor-in-chief of the four-volume Encyclopaedia of The American Constitution. In his 1999 Origins of the Bill of Rights he described the political background and intent of most of the amendments in the Bill of Rights.

Leonard Levy was a historian, not a historicist, and his body of work illustrates the difference between these two approaches to understanding and using the past. The New York Times wrote that "Professor Levy had a gloomy side, and he sometimes despaired over whether his mountain of scholarship had had an impact." This is because much of the legal academy today is decidedly historicist in its approach to constitutional history, viewing historical investigation as being in service of today's ideological agenda. As such, Levy's scrupulous approach was an obstacle, and is not emulated. But his work and example will remain a model for thoughtful scholars so long as honesty still exists in the academy, and his many grateful students will never forget him.

Blasphemy means speaking evil of sacred matters. Where organized religion exists, blasphemy is taboo. Thus, monotheistic religions have no monopoly on the concept of blasphemy. Any pagan society, whether as civilized as ancient Egypt or as primitive as idol-worshipping natives on Papua, can imagine superior beings or spirits that influence man's destiny; every religious society will punish the rejection or reviling of its gods. Because blasphemy is an intolerable profanation of the sacred, it affronts the priestly class, the deep-seated beliefs of worshippers, and the basic values that a community shares. Punishing the blasphemer may serve any one of several social purposes in addition to setting an example to warn others. Punishment propitiates the offended deities by avenging their honor, thereby averting divine wrath: earthquakes, infertility, lost battles, floods, plagues, or crop failures. Public retribution for blasphemy also vindicates the witness of the believers and especially of the priests; it reaffirms communal norms; and it avoids the snares of toleration.

I nonetheless maintain that language and not politics was the crucial question here. Salman Rushdie, raised a Muslim, concluded that the Koran was a book made by the hands of men and was thus a fit subject for literary criticism and fictional borrowing. (Almost every historic battle for free expression, from Socrates to Galileo, has begun as a struggle over what is and is not “blasphemy.”) In contrast, the very definition of a “fundamentalist” is someone who believes that “holy writ” is instead the fixed and unalterable word of god. For our time and generation, the great conflict between the ironic mind and the literal mind, the experimental and the dogmatic, the tolerant and the fanatical, is the argument that was kindled by The Satanic Verses.Not everybody agreed with me about the nature of this confrontation. President George H. W. Bush, asked for a comment, said that no American interest was involved. I doubt he would have said this if the chairman of Texaco had been hit by a fatwa, but even if Salman’s wife of the time (who had to go with him into hiding) had not been an American, it could be argued that the United States has an interest in opposing state-sponsored terrorism against novelists. Various intellectualoids, from John Berger on the left to Norman Podhoretz on the right, argued that Rushdie got what he deserved for insulting a great religion. (Like the Ayatollah Khomeini, they had not put themselves to the trouble of reading the novel, in which the only passage that can possibly be complained of occurs in the course of a nightmare suffered by a madman.) Some of this was a hasty bribe paid to the crude enforcer of fear: if Susan Sontag had not been the president of pen in 1989, there might have been many who joined Arthur Miller in his initial panicky refusal to sign a protest against the ayatollah’s invocation of Murder Incorporated. “I’m Jewish,” said the author of The Crucible. “I’d only help them change the subject.” But Susan would have none of that, and shamed many more pants wetters whose names I still cannot reveal. Others remarked darkly that Rushdie “knew what he was doing,” as if that itself was something creepy or mercenary on its face. By the way, he certainly did know what he was doing. He had studied Islamic scripture at Cambridge University, and I well remember one evening, at the apartment of Professor Edward Said near Columbia, when the advance manuscript of The Satanic Verses was delivered to Edward by the Andrew Wylie agency. In a covering note, Salman asked America’s best-known Palestinian for his learned advice, given the probability that the book might upset “the faithful.” So, yes, he “knew” all right, but in a highly responsible way. In any case, it is not the job of writers and thinkers to appease the faithful. And the faithful, if in fact upset or offended, are quite able and entitled to explore all forms of protest. Short of violence.

William Blake expressed the proper attitude of religious people toward satirical blasphemy. Those who believe they hold an eternal truth about the nature and destiny of the universe cannot find a cartoon or novel to be genuinely threatening. The Parthenon or the Great Pyramid is not destroyed by some graffiti scrawled on its base. Equanimity is one manifestation of mature faith.The discrediting of religion is usually an inside job -- often by religious people who allow their faith to be exploited in pursuit of someone else's ideological agenda. Think of the "German Christians" who applauded Adolf Hitler's rise in the 1930s. "Our Protestant churches have welcomed the turning point of 1933," said one Lutheran theologian, "as a gift and miracle of God." What vulgar anti-religious satire, what urine-soaked crucifix, could possibly be more damaging than this?The murders at Rue Nicolas-Appert are part of a similar story: the exploitation of religious passions for political ends. This is what separates Islam from violent Islamism (or whatever term one applies to the political ideology that inspires the killing of cartoonists and the Islamic State's reign of terror). Some Islamists have a history of using blasphemy -- real or imagined -- to cultivate grievances and motivate political violence."The phenomenon of outrage over insults to Islam and its final prophet is a function of modern-era politics," Husain Haqqani, Pakistan's former ambassador to the U.S., has explained. "It started during Western colonial rule, with Muslim politicians seeking issues to mobilize their constituents. Secular leaders focused on opposing foreign domination, and Islamists emerged to claim that Islam is not merely a religion but also a political ideology. Threats to the faith became a rallying cry for the Islamists, who sought wedge issues to define their political agenda."

Excerpt from, "The Disappeared" by Salman Rushdie, The New Yorker, September 10, 2012:

The book took more than four years to write. Afterward, when people tried to reduce it to an “insult,” he wanted to reply, “I can insult people a lot faster than that.” But it did not strike his opponents as strange that a serious writer should spend a tenth of his life creating something as crude as an insult. This was because they refused to see him as a serious writer. In order to attack him and his work, they had to paint him as a bad person, an apostate traitor, an unscrupulous seeker of fame and wealth, an opportunist who “attacked Islam” for his own personal gain. This was what was meant by the much repeated phrase “He did it on purpose.” Well, of course he had done it on purpose. How could one write a quarter of a million words by accident? The problem, as Bill Clinton might have said, was what one meant by “it.”

The ironic truth was that, after two novels that engaged directly with the public history of the Indian subcontinent, he saw this new book as a more personal exploration, a first attempt to create a work out of his own experience of migration and metamorphosis. To him, it was the least political of the three books. And the material derived from the origin story of Islam was, he thought, essentially respectful toward the Prophet of Islam, even admiring of him. It treated him as he always said he wanted to be treated, not as a divine figure (like the Christians’ “Son of God”) but as a man (“the Messenger”). It showed him as a man of his time, shaped by that time, and, as a leader, both subject to temptation and capable of overcoming it. “What kind of idea are you?” the novel asked the new religion, and suggested that an idea that refused to bend or compromise would, in all likelihood, be destroyed, but conceded that, in very rare instances, such ideas became the ones that changed the world. His Prophet flirted with compromise, then rejected it, and his unbending idea grew strong enough to bend history to its will.

When he was first accused of being offensive, he was truly perplexed. He thought he had made an artistic engagement with the phenomenon of revelation—an engagement from the point of view of an unbeliever, certainly, but a genuine one nonetheless. How could that be thought offensive? The thin-skinned years of rage-defined identity politics that followed taught him, and everyone else, the answer to that question.

Excerpt from, "Rushdie was tight-fisted and arrogant, with a handshake like a wet fish, says Special Branch officer who knew him as Scruffy" Evening Standard, July 26, 2008:

Scruffy said he wanted to publish a book about his life under this death sentence and his experiences of being protected by Special Branch.It infuriated me. We were protecting him in undoubtedly the most expensive operation of its type ever staged and he wanted to make bucketloads of money by writing about us.Scruffy was told the book might inflame matters by giving the impression that he was making a profit out of his alleged blasphemy.